MISMATCHED STATION

This Month’s Q&A was submitted by FAH member, Elliott M. Warburton, a young historian attending A.I. DuPont High School.

Photographic records of the stations along the original Wilmington & Western Rail Road thankfully exist for all stations. Pictured is an Intaglio engraving produced print of the railroad’s first Wilmington Station (left) and Wilmington Freight Depot (right) from Lippincotts Magazine, April 1873 showing typical construction. We can confirm that the stations that once stood along the line were mostly identical, and all appeared similar to our community’s beloved Yorklyn Station. That is, except for one. There is one station, known to have stood alongside the Branch, that is completely different in design from not only Yorklyn Station, but every other station constructed along the line. It appears to be, in an 1895 photograph by Charles Philips, a two-story, peaked roof structure, with absolutely no similarities to Yorklyn Station or any of the others at all. What station is this, and why is it so different from any other station along the line?

Answer

Throughout the history of Yorklyn, there have been numerous structures that have architecturally become staples of the community. Within this category, we have places like Auburn Heights, various Garrett homes, and when looking back at what once was in Yorklyn, numerous ornate mills that emphasized architecture (Garrett Snuff Mill below; E. Christofano 1986) as much as they did production capabilities. One important structure, which is no longer within the boundaries of Yorklyn (but nevertheless holds much value to our community), is the Wilmington & Western Rail Road’s (WWRR) Yorklyn Station, which was moved to Greenbank in 1968. The structure was moved following Tom Marshall’s and other’s interest in the Baltimore & Ohio’s Landenberg Branch, to revive branch steam passenger service between Greenbank and Hockessin (Landenberg, the end of the original Wilmington & Western, was inaccessible by rail following the 1950s removal of the right-of-way after Valley Road in Hockessin).

Throughout the history of Yorklyn, there have been numerous structures that have architecturally become staples of the community. Within this category, we have places like Auburn Heights, various Garrett homes, and when looking back at what once was in Yorklyn, numerous ornate mills that emphasized architecture (Garrett Snuff Mill below; E. Christofano 1986) as much as they did production capabilities. One important structure, which is no longer within the boundaries of Yorklyn (but nevertheless holds much value to our community), is the Wilmington & Western Rail Road’s (WWRR) Yorklyn Station, which was moved to Greenbank in 1968. The structure was moved following Tom Marshall’s and other’s interest in the Baltimore & Ohio’s Landenberg Branch, to revive branch steam passenger service between Greenbank and Hockessin (Landenberg, the end of the original Wilmington & Western, was inaccessible by rail following the 1950s removal of the right-of-way after Valley Road in Hockessin).

But another reason the station was relocated was for proper preservation by dedicated enthusiasts. The only reason the station survived as long as it did was due to the freight services NVF still needed into the 1960’s, and the desire to have an office close to the primary remaining freight operation along the branch. Yorklyn Station was, in reality, one of nine nearly identical stations constructed by the first incarnation of the Wilmington & Western between its Wilmington origin, and it’s Landenberg terminus.

Ironically, for Landenberg station, constant relocation of the WWRR’s Wilmington Station eventually resulted in the first WWRR Wilmington Station being disassembled and reassembled in Landenberg to become Landenberg Station. As a result of the flat-roofed design of the stations, and the probability of lack of routine maintenance to all the stations in times of financial difficulty or when they were closed, Yorklyn Station became the sole surviving station by the mid-20th century. Hockessin Station, of similar design to Yorklyn Station, became the only remaining station when Hockessin Station was torn down in 1950.

Ironically, for Landenberg station, constant relocation of the WWRR’s Wilmington Station eventually resulted in the first WWRR Wilmington Station being disassembled and reassembled in Landenberg to become Landenberg Station. As a result of the flat-roofed design of the stations, and the probability of lack of routine maintenance to all the stations in times of financial difficulty or when they were closed, Yorklyn Station became the sole surviving station by the mid-20th century. Hockessin Station, of similar design to Yorklyn Station, became the only remaining station when Hockessin Station was torn down in 1950.

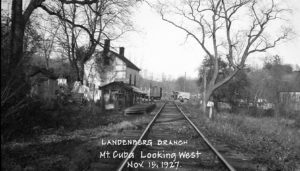

The station in question, once standing near Mt. Cuba Road covered bridge, was the primary station for the Mt. Cuba community on the Christiana and Mill Creek Hundred sides of the Red Clay. It appears in an 1895 photograph by Charles Philips (shown right and close-up below, ca. 1890s, from Charles Philips Collection at Chester County Historical Society) as a two-story, peaked roof structure, with absolutely no similarities to Yorklyn Station at all. What makes Mt. Cuba’s station different from the station at Yorklyn can mainly be accredited to the fact that the structure was not actually erected by the original incarnation of the Wilmington & Western (1869-1877), but was a pre-existing structure, likely a private residence, repurposed for the railroad at Mt. Cuba.

Mt. Cuba Station actually represents a unique case in the original WWRR’s history when the company decided to use an existing structure for their infrastructure, rather than fabricate an entirely new building, as they had for every other depot along the line. Why the company may have chosen to do this may have been a result of their financial difficulties during the railroad’s construction, which possibly impaired the Company’s ability to erect a new station at Mt. Cuba (or Cuba Hill, a name often exchanged with Mt. Cuba until 1872). It is important to keep in mind that Mt. Cuba rock cut, the monstrously challenging final roadblock of the line, was within the vicinity of the station. On a railroad that started construction crews at Wilmington and Landenberg in 1871 and laid rails west and east respectively until they met at Mt. Cuba, further construction within the area had become a costly and potentially bankrupting effort for the railroad.

Mt. Cuba Station actually represents a unique case in the original WWRR’s history when the company decided to use an existing structure for their infrastructure, rather than fabricate an entirely new building, as they had for every other depot along the line. Why the company may have chosen to do this may have been a result of their financial difficulties during the railroad’s construction, which possibly impaired the Company’s ability to erect a new station at Mt. Cuba (or Cuba Hill, a name often exchanged with Mt. Cuba until 1872). It is important to keep in mind that Mt. Cuba rock cut, the monstrously challenging final roadblock of the line, was within the vicinity of the station. On a railroad that started construction crews at Wilmington and Landenberg in 1871 and laid rails west and east respectively until they met at Mt. Cuba, further construction within the area had become a costly and potentially bankrupting effort for the railroad.

Another possible reason the structure may have been repurposed as a station could have been out of pure coincidence. It was in the Wilmington & Western’s best interest to build a railroad at least cost, or essentially, the easiest way possible. Unfortunately, the area around Mt. Cuba Road offers few places to go besides directly in front of what was then a private residence (see map below).

The residence, as deduced from maps and records, was likely constructed by one J. Curley between 1850 and 1865. The property changed hands from Curley to a more established Mt. Cuba resident, Thomas Vandever, sometime between 1868 and 1872. Vandever, a prosperous farmer in the Mt. Cuba area, may have seen the railroad’s approach as a chance to buy up as much land adjacent to the creek as possible in order to make a profit; a common real estate tactic at the time.

The residence, as deduced from maps and records, was likely constructed by one J. Curley between 1850 and 1865. The property changed hands from Curley to a more established Mt. Cuba resident, Thomas Vandever, sometime between 1868 and 1872. Vandever, a prosperous farmer in the Mt. Cuba area, may have seen the railroad’s approach as a chance to buy up as much land adjacent to the creek as possible in order to make a profit; a common real estate tactic at the time.

In the case of the “Curley Home,” Vandever perhaps saw the property as a chance to potentially provide a depot to the railroad in order to ship his and his neighbor’s farm goods at the least cost to the community. If a new station needed to be constructed, it might be expected a station might’ve been built farther away from the Mt. Cuba farmers. Because of this, Vandever likely purchased the home, and within a short time of his acquisition, released it to the railroad for official public use. This situation, using a pre-existing structure for a new and important role, provided a unique opportunity for the local community to use a structure in a multitude of different roles.

We commonly view Yorklyn Station as being utilitarian during its time in Yorklyn. Yorklyn Station was railroad property from its construction to its final days in its original home in 1968. But as for Mt. Cuba Station, after being a private residence, the structure became a focal point of community activities, not only providing a rail connection to Wilmington and beyond, but providing a place for auctions, public gatherings, and other events of interest. Not to mention, a system of sidings (north of Mt. Cuba Road, shown on map) at Mt. Cuba were some of the largest along the line that weren’t tied to production facilities like Garrett Snuff Mills or the Marshall Rolling Mills in Marshallton. Mt. Cuba Station acted as one of the most capable places along the line for processing livestock, farm products, and smaller local milling shipments. It is also known that the station acted as one of the major centers for the region’s milk shipments along the WWRR. Just beyond the station was a picnic grove, still in use today, that the Wilmington & Western used heavily for special events and excursions in the 1870s.

We commonly view Yorklyn Station as being utilitarian during its time in Yorklyn. Yorklyn Station was railroad property from its construction to its final days in its original home in 1968. But as for Mt. Cuba Station, after being a private residence, the structure became a focal point of community activities, not only providing a rail connection to Wilmington and beyond, but providing a place for auctions, public gatherings, and other events of interest. Not to mention, a system of sidings (north of Mt. Cuba Road, shown on map) at Mt. Cuba were some of the largest along the line that weren’t tied to production facilities like Garrett Snuff Mills or the Marshall Rolling Mills in Marshallton. Mt. Cuba Station acted as one of the most capable places along the line for processing livestock, farm products, and smaller local milling shipments. It is also known that the station acted as one of the major centers for the region’s milk shipments along the WWRR. Just beyond the station was a picnic grove, still in use today, that the Wilmington & Western used heavily for special events and excursions in the 1870s.

The appearance of the station as different and older, though contrary to railroad President Joshua Heald’s view on WWRR stations, is an important reminder to some of the decisions made by the Wilmington & Western Rail Road during its construction period. But more importantly to us, Mt. Cuba Station shows exactly how crucial these structures were for the communities they served. Though different in design, the Mt. Cuba Station still proved an important community center for Mt. Cuba, similar to how we have come to retrospectively view Yorklyn Station as the center of our community when we still had the chance to have it nearby.

With the closure of places like the Mt. Cuba Picnic Grove by 1900, the town lost an important tourist attraction that drew people to the community. A 1927 Baltimore & Ohio photograph of the station (above right), the best one that can be produced of the site, shows the aging structure falling into disrepair, far beyond any state of grandeur as an original WWRR station. Officially, a benchmark date for the “dissolution” of the Mt. Cuba community could be seen as July 15, 1933 when the community’s post office officially closed. Without passenger service, which had been discontinued in 1930, it is assumed the station and home fell into disrepair. Due to the absence of any visible infrastructure at Mt. Cuba revealed on Delaware State Aerial Photographs from 1937, it can be assumed the 80-year-old home and station were lost to the same fate as stations like Ashland, Hockessin, and Landenberg (pictured below just before razing; New Garden Historical Society), leaving Yorklyn Station as yet another important survivor of the railroading age of the Red Clay Valley.

With the closure of places like the Mt. Cuba Picnic Grove by 1900, the town lost an important tourist attraction that drew people to the community. A 1927 Baltimore & Ohio photograph of the station (above right), the best one that can be produced of the site, shows the aging structure falling into disrepair, far beyond any state of grandeur as an original WWRR station. Officially, a benchmark date for the “dissolution” of the Mt. Cuba community could be seen as July 15, 1933 when the community’s post office officially closed. Without passenger service, which had been discontinued in 1930, it is assumed the station and home fell into disrepair. Due to the absence of any visible infrastructure at Mt. Cuba revealed on Delaware State Aerial Photographs from 1937, it can be assumed the 80-year-old home and station were lost to the same fate as stations like Ashland, Hockessin, and Landenberg (pictured below just before razing; New Garden Historical Society), leaving Yorklyn Station as yet another important survivor of the railroading age of the Red Clay Valley.